Embedding Assessment into Daily Activities and Routines

Feel free to print and/or copy any original materials contained in this packet. KITS has purchased the right to reproduce any copyrighted material included in this packet. Any additional duplication should adhere to appropriate copyright law.

The example organizations, people, places, and events depicted herein are fictitious. No association with any real organization, person, places, or events is intended or should be inferred.

Compiled by Cindy Kongs M.S., Misty D. Goosen, Ed.S., Phoebe Rinkel, M.S. and David P. Lindeman, Ph.D.

December 2011

Kansas Inservice Training System

Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities

Adapted for accessibility and transferred to new website October 2022

Kansas Inservice Training System is supported though Part C, IDEA Funds from the Kansas Department of Health and Environment.

The University of Kansas is and Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action Employer and does not discriminate in its programs and activities. Federal and state legislation prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, religion, color, national origin, ancestry, sex, age, disability, and veteran status. In addition, University policies prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, marital status, and parental status.

Letter from the Director

December 2011

Dear Colleague,

Infant toddler networks and school districts serving young children with special needs collect and submit Early Childhood Outcome (ECO) data to the Kansas Department of Health and Environment (KDHE) and the Kansas State Department of Education (KSDE) to fulfill federal accountability requirements for IDEA programs. KDHE and KSDE have instructed early intervention networks and school districts to use results from one of eight identified curriculum based assessment (CBA) tools when measuring and reporting ECO data. CBA measures are useful beyond the new ECO requirement. Specifically, these tools can be used for ongoing assessment of the progress of individual or groups of children. This will provide data necessary to adapt or change instructional strategies and support children in achieving desired outcomes. Information gathered from observation and curriculum-based assessment can be useful in reporting child progress on Individual Education Plan (IEP) goals or Individual Family Service Plan (IFSP) outcomes. For preschoolers, CBA data can be used to document a child’s present levels of academic achievement and functional performance, and to demonstrate the child’s “involvement and progress in the general education curriculum” as prescribed by law (IDEA, 2004, Title I, B, 614 [d] 1 AiI ([a]). Also, results of CBA measures over time can be used for evaluating program impact on children’s developmental and behavioral performance and early school success.

This packet describes a process of ongoing assessment techniques for monitoring individual child performance in preschool on a regular and frequent basis. In this packet, the Assessment, Evaluation, and Programming System (AEPS) is used as one example of how CBA can be embedded into ongoing activities and routines in a preschool classroom. The use of the AEPS for illustrative purposes in this packet does not constitute an endorsement of this tool over any of the other state identified CBA measures. Any CBA can be used in a similar manner.

We hope that you will find that the packet contains helpful information. After you have examined the packet, please complete the evaluation found at the end of this packet. Thank you for your interest and your efforts toward the development of quality services and programs for young children and their families.

Sincerely,

David P. Lindeman, Ph.D.

KITS Director

Introduction to Embedding Assessment into Daily Activities and Routines

Early interventionists and early childhood special educators are often asked why they are doing what they are doing. One answer can be that their professional organization has identified certain practices as evidence-based and best practices. This packet reflects recommendations from the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) and the Division for Early Childhood (DEC) of the Council for Exceptional Children.

Information contained in this technical assistance packet supports the following NAEYC professional guidelines for professionals in early childhood education (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009).

- Guideline 3: A1. Teachers consider what children should know, understand, and be able to do across the domains of physical, social, emotional, and cognitive development and across the disciplines, including language, literacy, mathematics, social studies, science, art, music, physical education, and health (p. 20)

- Guideline 3: A2. If state standards or other mandates are in place, teachers become thoroughly familiar with these (p. 20) • Guideline 4: Assessment of children’s development and learning is an essential for teachers and programs in order to plan, implement, and evaluate the effectiveness of the classroom experiences they provide. Assessment also is a tool for monitoring children’s progress toward a program’s desired goals. … Teachers cannot be intentional about helping children to progress unless they know where each child is with respect to learning goals (p. 21-22).

- Guideline 4:A. Assessment of young children’s progress and achievements is ongoing, strategic, and purposeful. The results of assessment are used to inform the planning and implementation of experiences, to communicate with the child’s family, and to evaluate and improve teachers’ and the program’s effectiveness (p. 22).

- Guideline 4:C. There is a system in place to collect, make sense of, and use the assessment information to guide what goes on in the classroom (formative assessment). Teachers use this information in planning curriculum and learning experiences and in moment-to-moment interactions with children—that is, teachers continually engage in assessment for the purpose of improving teaching and learning (p.22).

- Guideline 4:E. Assessment looks not only at what children can do independently buy also at what they can do with assistance from other children or adults. Therefore, teachers assess the children as they participate in groups and other situations that are providing scaffolding (p. 22)

Information contained in this technical assistance packet supports the following DEC recommended practices for professionals in early childhood special education and early intervention (Sandall, Hemmeter, Smith, & McLean, 2005).

- A13. Professionals use multiple measures to assess child status, progress, and program impact and outcomes (e.g., developmental observations, criterion/curriculum-based, interviews, informed clinical opinion, and curriculum-compatible norm referenced scales). (p. 53)

- A15. Professionals rely on materials that capture the child’s authentic behaviors in routine circumstances (p. 54).

- A17. Professionals assess children in contexts that are familiar to the child (p. 54).

- A20. Professionals assess the child’s strengths and needs across all developmental and behavioral dimensions (p. 55).

- A24. Professionals assess not only immediate mastery of a skill, but also whether the child can demonstrate the skill consistently across other settings and with other people (p. 56).

- A27. Professionals and families rely on curriculum-based assessment as the foundation or “mutual language” for team assessments (p. 57).

- A28. Professionals conduct longitudinal, repeated assessments in order to examine previous assumptions about the child and to modify the ongoing program (p. 57).

- A41. Professionals monitor child progress based on past performance as the referent rather than on group norms (p. 60). • A44. Professionals and families conduct an ongoing (formative) review of the child’s progress at least every 90 days in order to modify instructional and therapeutic strategies (p. 61).

- A45. Professionals and families assess and redesign outcomes to meet the ever changing needs of the child and family (p. 61).

- A46. Professionals and families assess the child’s progress on a yearly (summative) basis to modify the child’s goal-plan (p. 61).

One of the most important yet neglected responsibilities in the field of early childhood is the ongoing assessment of individual and group progress in relation to the classroom curriculum. Ongoing assessment refers to the frequent and systematic collection and analysis of data to determine child progress and make instructional decisions that will support and promote the achievement of identified child outcomes. Early childhood professionals often report they do not have enough time to continually assess and reassess all of the children for whom they are responsible. While the creation of a system for ongoing assessment of child progress may seem daunting, early childhood professionals cannot absolve themselves of this important responsibility. Not only are there legal requirements for reporting progress to parents of children with IEPs (at least as often as progress reports are made to students in general education, IDEA 2004), recommended practices for early childhood special education call for repeated assessment of children across “all developmental and behavioral dimensions” (Sandall, Hemmeter, Smith, & McLean, 2005, p. 55) in order to “examine previous assumptions about the child, and to modify the ongoing program” (Sandall, et al., p. 57).

NAEYC guidelines (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009) suggest that all early childhood teachers should be highly intentional in their focus on the key skills and behaviors children need to acquire in order to make optimal progress. Teachers can only be intentional if they know where each child is performing in relation to curriculum goals. This calls for a system for collecting, recording, interpreting, and using assessment information to improve teaching and learning in the classroom. To benefit from early childhood programs, young children must be engaged in learning opportunities that are developmentally and individually appropriate, child centered, actively engaging and challenging (Sandall, et al., 2005). This cannot be done randomly, and therefore requires purposeful planning, based on ongoing assessment that is anchored in child development and linked to curricular content. Although not a curriculum, the Kansas Early Learning document (2009) provides an overview of the sequential skills and behaviors young children should have and can learn in order to be successful in kindergarten and beyond.

There is a plethora of information and guidance regarding recommended practices for ongoing assessment of progress for young children with disabilities (Sandall, et al., 2005; Sandall, Giacomini, Smith, & Hemmeter, 2006; Sandall & Schwartz, 2008) Likewise there are guidelines and resources to support ongoing assessment of children who are typically developing in preschool settings (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009). What is needed to support the inclusion of children with IEPs in settings with their typical peers are specific, effective strategies for monitoring the progress of all children in a classroom toward the accomplishment of general education curriculum goals.

Therefore, the purpose of this packet is to suggest strategies for ongoing assessment that can be carried out within the context of a developmentally appropriate preschool classroom that includes children with a wide range of abilities, some with IEPs. Sample activities are provided to illustrate ways in which teachers can effectively and efficiently collect and use data to make instructional decisions aimed at improving outcomes for all children. Proactively designing and scheduling ongoing assessment activities linked to the curriculum and early learning standards helps to ease the burden felt by early childhood professionals, and allows them to collect the information needed to continually adapt learning opportunities and interventions for individuals and groups of children in their classroom.

The Good News

One of the most difficult tasks in designing a system for monitoring ongoing progress is choosing assessment tools and strategies that are appropriate for young children and will provide meaningful and useful information. The good news for special education professionals in Kansas is that, due to the ECO reporting requirement, programs serving young children with disabilities should already be collecting information and using assessment tools designed for this purpose. In 2006, school districts serving young children with disabilities were required to select and begin using a curriculum based assessment (CBA) tool from one of the following eight approved measures:

- Assessment and Evaluation Programming System (AEPS)

- Carolina Curriculum

- Child Observation Record (High Scope)

- Creative Curriculum

- Hawaii Early Learning Profile (HELP

- Individual Growth and Development Indicators (IGDIs)

- Transdisciplinary Play Based Assessment

- Work Sampling System

Districts were instructed to use their selected CBA as a part of the initial evaluation and subsequent re-evaluation of children entering and exiting a Part B (Preschool) program. Kansas requires the CBA be administered at only two points (entry into the Part B Program, Part B Program), however these tools can be much more useful to programs when they are administered more frequently with the express purpose of monitoring goal attainment and to document progress in a general education curriculum aligned with state early learning standards.

While having and using a CBA is a major step toward developing an ongoing assessment system, teachers and other early childhood professionals must have a good understanding of where such measures fit into the overall standards-based curricular framework. They must also be able to identify how their CBA tool can be used as a developmentally appropriate assessment practice embedded in everyday activities/routines, and be able to prioritize the skills and knowledge that children should demonstrate as they move through the early childhood programs. They must be able to employ a system that allows children’s performance to be easily assessed, recorded and analyzed. Many of the Kansas approved CBA tools provide these elements. The Assessment, Evaluation, and Programming System (AEPS) is one such tool.

Based on the first author’s extensive classroom experience with the AEPS, and because it has been aligned with the Kansas Early Learning standards (Please visit AEPS Interactive for the latest state standards). It is used to illustrate how districts can utilize a CBA as a focal point for creating an ongoing assessment system. The use of the AEPS examples does not imply an endorsement of this measure by KITS over other CBA tools.

Information about all eight of the curriculum-based assessments approved for use in reporting child progress on Early Childhood Outcomes can be viewed on this KITS website.

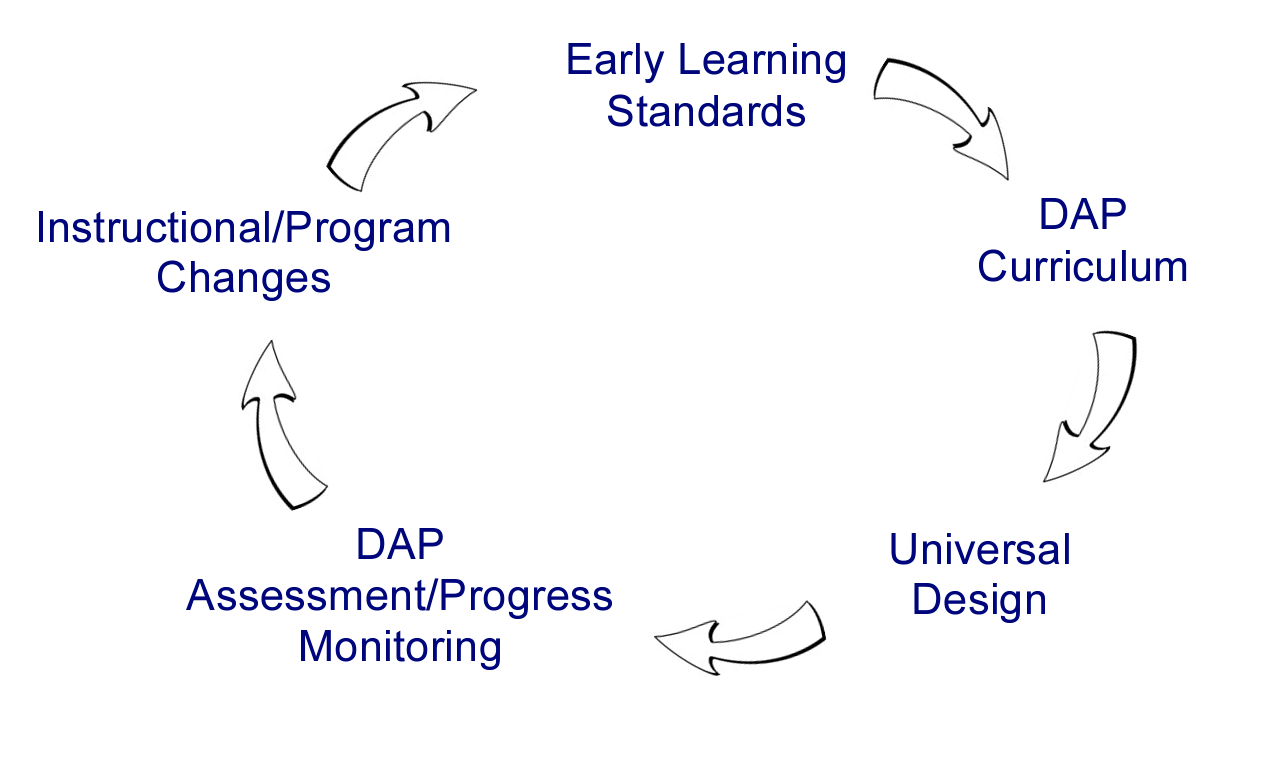

Standards Based Curricular Framework

A standards based curricular framework is the blueprint for implementing state identified early learning standards. State standards are implemented through the use of an aligned curriculum that is utilized to meet group and individual needs through a system of ongoing assessment and data analysis. Therefore all the components of the framework are linked and move in a continuous improvement pattern.

The following provides a more in-depth look at the specific elements within a standards based curricular framework outlining how each step contributes to quality programming for all young children and their families.

Early Learning Standards

Professionals and families are well aware of the standards movement that has swept across our nation’s elementary and secondary school systems in the last decade. States were directed to develop and implement high academic standards from which yearly progress could be gauged and overall performance of the educational system could be evaluated. The idea of high standards did not stop with elementary and secondary school systems. With the passage of “No Child Left Behind” and other education initiatives states were once again directed to develop and implement learning standards, this time for its youngest citizens. Kansas began the task in 2003, published the Kansas Early Learning Document (KSELD) in the fall of 2006, and revised the document in 2009. Visit KSDE for the latest KSELD information.

The KSELD is divided into two sections: 1) Early Learning Guidelines (KSELD-ELG), and 2) Early Learning Standards (KSELD-ELS). The KSELD-ELG provides a general overview and examples of some of the skills and knowledge children should possess at certain ages. The KSELD-ELS provides broad statements of what children should know and be able to do as a result of attending a high quality early learning program.

A Closer Look at the KSELD-ELS

The KSELD-ELS was created by a diverse group of early childhood stakeholders using current research and evidence regarding early learning. It serves as a framework for designing and implementing meaningful curricula and intentional learning experiences by outlining a specified scope and sequence from which broad learning goals and individual needs can be identified and measured against. It was created with an understanding that young children grow and develop at a wide and variable rate, and reflects the need to connect learning to both developmental and content areas (Grisham-Brown, Hemmeter & Pretti-Frontczak, 2005).

The KSELD-ELS is divided into eight developmental content areas:

- Physical Development

- Social Emotional Development

- Communication & Literacy

- Approaches to Learning

- Science

- Mathematical Knowledge

- Social Studies

- Fine Arts

Within each of the content areas specific standards, benchmarks and indicators are provided. The standards are statements describing the expectations for skills and knowledge that young children ages birth through five should know and be able to do as a result of participating in high quality early childhood programs. Benchmarks break the standard down into increments, and are used to gauge child progress toward meeting the standard. Indicators follow each benchmark and are example behaviors of knowledge or skills that children might demonstrate at different levels of development in order to meet the benchmark.

The KSELD-ELS reflects a wide range of abilities and expectations, and helps create a common language from which to discuss children’s capabilities and accomplishments. It provides a framework for accountability; however, the primary purpose is to improve instruction. While standards help identify what children should know and be able to do, they don’t provide methods for achieving the standard, nor do they address how progress will be assessed. Therefore, accomplishment of the standards relies on the alignment and implementation of a developmentally appropriate curriculum and authentic assessment practices. Authentic assessment refers to “the systematic collection of information about the naturally occurring behaviors of young children and families in their daily routines” (Neisworth & Bagnato, 2004, p. 203).

Developmentally Appropriate Curriculum Aligned to the KSELD-ELS

To benefit from early childhood programs young children must be engaged in learning opportunities that are: 1) developmentally and individually appropriate, 2) child centered, and 3) actively engaging and challenging (Sandall, Hemmeter, Smith & McLean, 2005). Therefore a developmentally appropriate curriculum is designed to promote learning environments that are responsive, predictable, challenging and provide multiple opportunities for learning through activities that have been matched to the interests and needs of individual children. The following are characteristics of a high quality program utilizing a developmentally appropriate curriculum:

- Schedules are divided into segments appropriate to children’s needs and include outdoor time

- Activities are balanced between active/quiet/ child-initiated/teacher directed

- Opportunities for large /small group participation, as well time alone or with friends

- Adequate time for routines (e.g. toileting, snacks and transitions)

- Learning environments are designed utilizing the principles of universal design

- The daily routine, play opportunities and transition activities are structured to promote interaction and communication

- Adults are responsive to the child and expand on the child’s play/behavior

(Conn-Powers, Cross, Traub, & Hutter-Pishgahi, 2006; Sandall, et al., 2005; Fox, Dunlap, Hemmeter, & Strain, 2003; Brown, Odom, & Conroy, 2001; Schwartz, Carta, & Grant, 1996; Wolery & Wilbers, 1994). For more information on Developmentally Appropriate Practices, you can view the 2011 KITS technical assistance packet on the topic under the Virtual Kits section of this website.

Young children learn best through learning opportunities that are integrated, build on their interests, and allow for the development of knowledge and skills in activities that are meaningful to their lives (Grisham-Brown, et al., 2005). Such learning opportunities do not happen randomly. They require purposeful planning rooted in child development and based on the most current research, all of which can be achieved through the implementation of a developmentally appropriate curriculum.

Curriculum provides specific information regarding how, when, where, and under what circumstances children will achieve the early learning standards. Curriculum provides direction for organizing and planning teaching through daily activities, identification of specific materials, environmental arrangement, and utilization of specific intervention strategies. Curriculum extends the standards by addressing additional learning goals that fit within the learning theory from which the curriculum was constructed.

While the curriculum identifies how the standards will be achieved, assessment activities help determine if learning has been accomplished, and if not, provides information regarding what still must be taught and/or what changes need to be made in specific teaching practices.

Universal Design

Universal design for learning (UDL) is a broad term used to describe the proactive planning and creation of learning opportunities that allow all children to access, participate in and benefit from the general education curriculum as required in the IDEA amendments of 2004, increasing the likelihood of positive outcomes for all children (DEC, 2007). In anticipation of the wide range of abilities/differences among each and every learner, the teacher designs the learning content, environment and assessment activities in such a way that all children can be involved in the learning experiences (Rose & Meyer, 2000).

The essential components of a curriculum framework based on universal design for learning would include:

- Multiple means of representation (e.g., how information and content can be presented)

- Multiple means of engagement (e.g., how to interest students in learning and motivate them to stay interested)

- Multiple means of expression (e.g., how students can demonstrate what they have learned)

For more information about UDL visit the Center for Applied Special Technology/CAST.

Developmentally Appropriate Assessment Practices

The term assessment refers to the “process of gathering information for the purposes of making decisions” (McConnell, McEvoy, Carta, Greenwood, Kaminski, Good, Shinn, Ysseldyke, & Goldbert, 1998, p. 2.). Evaluation, on the other hand, is the process of making a decision based on specific assessment information (Bagnato, Neisworth, & Munson, 1997). Therefore, assessment and evaluation imply that, at some point, decisions will be made and some action will follow that will facilitate learning.

In the field of early childhood there are five general purposes for assessment and evaluation.

- Screening – (a) developmental screening: quick assessments used to determine if a child’s development/skills fall within an age expected range and if not determines a need for more comprehensive assessment and evaluation, (b) universal screening: quick assessments used to determine general skill levels within core curriculum areas. These assessments are administered to an entire class, grade level, etc. at specified times in the year (generally fall, winter, spring), and provide information that can be used to identify groups in need of further supplemental or intensive instruction.

- Eligibility Determination – Evaluation information and procedures used to determine if a child meets certain requirements that entitle him/her for specific services (e.g. early intervention/ special education).

- Program Planning – Assessments used to identify a child’s present level of function/ performance within the overall learning program, as well as specific strengths, needs, interests, or other information that can be used in the development of an individualized program (e.g. IEP).

- Progress Monitoring – Ongoing assessment methods and strategies used to track performance on specific targets, skills, or processes. This information is collected and analyzed frequently (e.g., alphabet awareness) or continuously (progress on CBA) in order to adapt teaching methods and facilitate learning, as well as for more formal reporting requirements (e.g. IEP progress monitoring as required by IDEA).

- Program Evaluation –Systematic assessment of the effects of the broad overall program practices on individual or groups of children. Information is used to evaluate program goals, highlight effective practices, identify the need for change in areas of weakness, plan for program improvement, determine professional development needs of staff, and ensure stakeholder satisfaction.

As mentioned earlier, curriculum-based assessment (CBA) is an effective way to gather information used for program planning and monitoring child progress in the general early education curriculum. CBA is a form of criterion-referenced measurement, which utilizes curriculum objectives as the “criteria” that serve as targets for instruction from which to assess status and monitor performance (Bagnato, 2007). CBA breaks up the curriculum into developmental hierarchies and domains, and often provides tools for recording achievement and mastery. These assessments illustrate where a child’s skills fall within each domain, providing a starting point for instruction and baseline information for ongoing assessment of progress.

CBA tools are either curriculum-referenced or curriculum-embedded. Curriculum-referenced assessments measure specific skills common to most curricula, but are not created from a specific curriculum. Curriculum-embedded assessments use specific curriculum content and objectives for assessment and teaching purposes. Therefore, professionals using a curriculum-embedded tool assess children using classroom activities and not a separate procedure, alleviating concern that children’s skills are being measured accurately and reflect a child’s true abilities (Bagnato, 2007). All eight of the Kansas approved CBAs are curriculum-embedded assessments and can be used for developmentally appropriate program planning and progress monitoring.

The AEPS tool is used in this packet to demonstrate how assessment can be embedded within curriculum based activities. However, the general steps and processes outlined here can be applied to any CBA to allow for continuous monitoring of objectives and learning goals.

Instructional/Program Changes

A final link in the process of ongoing assessment is the use of information that has been collected for the purpose of changing instructional practice for individual children and/or the entire class. For individual children who do not seem to be making appropriate progress, teachers can adjust/modify the environment, interactions, or activities and experiences to positively impact learning. When a large number of children are unable to reach identified learning goals in a specific domain, it may be necessary for the teacher to re-evaluate the appropriateness of the specific learning goals in question. If it is believed that the learning goals continue to be appropriate, then changes in the daily schedule, teaching strategies, styles of interactions, interest area arrangements, materials, or the design and implementation of small group work may be what is required. This information can also be used to re-evaluate the effectiveness of the overall curriculum (e.g. average performance of children within domains), and shared with family members, boards of directors or others who may support the ongoing needs of the preschool program.

Setting the Stage for Ongoing Assessment

This section contains:

- What’s Going on in the Classroom?

- What’s Going on During Outdoor Time?

- Steps to Developing an Ongoing System for Measuring Progress on CBAs

- Creating a Visual Map of Learning Goals/Objectives

- Using the AEPS Child Progress Record as a Visual Map

- Reviewing Classroom Schedules/Routines to Embed Assessment Activities

- Learning, Practice, Mastery

What's Going on in the Classroom?

In preparation for creating an ongoing curriculum based assessment system for the classroom, it is first necessary to review the developmentally appropriate learning opportunities and practices from which assessment activities may be identified and/or embedded.

- Child Initiated Activities: Child initiated activities provide an opportunity for children to self select activities they find highly enjoyable. These activities typically take place during “center-time” or “free-choice time” and are designed by the teacher to provide opportunities for children to become fully engaged with specific media or materials allowing plenty of time for practice and mastery of multiple skills. These types of activities provide an excellent opportunity to assess the progress or mastery of certain skills and provide a natural context in which children are likely to spontaneously exhibit the target skill without being directed to perform a task.

- Adult Directed Activities: For a portion of the preschool day children spend time in activities that are designed and directed by the teacher or other adults. Most often these activities are conducted through whole or small group instruction and, on occasion, individual instruction. Adult directed activities provide opportunities for the introduction of new concepts and a starting point for new skill development. These activities can be used to gather information regarding the type of targeted support a child may need to actually master new information.

- Whole Group Activities: Once or twice during a preschool session children may be gathered into one group to participate together as a classroom community. Circle time is one example of such an activity. Whole group activities promote a sense of community membership, provide an opportunity to practice group skills, and at times introduce themes and topics that will be expanded on throughout the course of the preschool day/week. Assessment within whole group activities provides more of a challenge for the teacher and therefore should be used minimally for this purpose. Whole group activities can be used to assess group membership skills such as sitting and listening to someone while speaking, choral responses, etc., but may not provide reliable opportunities for assessing content specific skills.

- Small Group Activities: Small group instruction is used to introduce new concepts or skills to a group of two to five children. Activities taking place in small groups provide excellent opportunities to assess children’s learning rate when they are presented new information. Small group activities also provide an opportunity to determine the types of assistance individual children need to acquire new skills, overall skill development 2 and mastery of the identified skills to be learned. It is important to keep in mind during which children are to be assessed must be highly motivating.

- Individual Instruction: In some instances and situations it may be appropriate and necessary to provide instruction to a single child. These situations should be limited to instances to support children in mastering very specific skills or tasks. This can also provide the adults in the classroom the opportunity to complete focused assessment. A critical feature to individual instruction will be the transfer of skills to general classroom activities and routines.

Example of Small Group Assessment Activity:

The following picture shows students playing Hasbro’s Candyland Castle™, a highly preferred activity in a preschool classroom, and one that provides opportunities for children to practice multiple skills across domains. In the small group pictured below, one child working on learning new skills, one child was practicing emerging skills, and the third child was generalizing skills previously mastered with a different game. For the students pictured, the teacher targeted the following skills for assessment, reflecting the range in their development.

- Fine motor: use of 3 finger grasp of small implement; use of both hands to perform different movements

- Gross motor: standing with support

- Cognition: understanding of colors, shapes, spatial and temporal relations concepts; sequencing; problem solving; engaging in game with rules

- Social communication: using language for various functions (e.g., to request, inform, direct, ask questions); using various grammatical forms (nouns, verbs, pronouns, descriptive words)

- Social: initiating and responding to social interaction; turn taking

- Routine Activities: Some activities take place every day as a part of the normal preschool routine. Routine activities such as arrival, snack, transitions, outdoor play, bathroom and dismissal provide opportunities for multiple observations of target skills. At times teachers may embed additional learning activities within a given routine to provide extra opportunities for practice or assessment of certain skills. For example during transition times between activities the teacher may engage children in short listening/imitation games where a small number of skills can be exhibited.

Helpful Idea: Transitions

Teachers can utilize smaller portions of the day to embed opportunities for practice and mastery of skills, which in turn lend themselves for data collection. One such example is transitions between activities. The challenge of a successful group transition is keeping children positively engaged until the next activity occurs with limited “sit and be quiet” wait time. Songs and movement activities used as part of the transition provide a perfect opportunity for additional practice and measurement of skills.

What’s Going On During Outdoor Time?

Typically, outdoor time is an unstructured period where children can engage in a variety of gross motor, fine motor and social skill activities. With a little planning, this time can be used to practice specific skills and allow for the collection of targeted curriculum assessment data.

Gross motor skills may not spontaneously occur or be easily measured in traditional free choice playground activities. Inserting a brief, five-minute planned activity at the beginning of each outdoor time along with the rotation of supplemental playground materials, can provide an opportunity for children to practice (and teachers to measure) specific gross motor skills.

Helpful Ideas: Assessing Gross Motor Skills

Traditional children’s games can be modified to fit targeted goals and objectives. “Red Light, Green Light” can be modified to include a wide variety of gross motor skills: running, running around obstacles, jumping with both feet, walking on tip-toes, hopping on one foot and/or skipping. To modify the game the leader announces the gross motor skill that will be used before saying “Green Light”. To assist preschool students in playing the modified version of “Red Light, Green Light” large red and green circles can be placed on large cards. The cards will provide students with a visual cue to start and stop. Picture cards with symbols and words can also be made for each targeted gross motor skill. To increase student participation, allow students to take turns choosing a specific gross motor skill from a few targeted skills. Once the game has been taught, the cards can be available during outdoor free time for students to use independently with a group of friends. Other games that can easily be modified include, but are not limited to: “Simon Says”, “Ring-Around-the-Rosie” and “Follow the Leader”.

Rotation of supplementary materials during outdoor time is another way to provide practice and measurement of gross motor, fine motor and social skills. Tubs of materials can be placed on the playground (e.g., assorted sizes of balls which lend themselves to throwing, catching or kicking, Frisbees, ring-toss, sidewalk chalk, koosh balls or bean bags with tubs or buckets to throw into, tricycles, scooters, sandbox toys and assorted paint brushes with buckets of water). Children will look forward to the addition of new materials, increasing the likelihood that they will participate, while the teacher has the opportunity to plan for specific skill practice/measurement.

Transition between activities is also a good time to practice or measure gross motor development. For examples, as students join circle time, have them practice standing/hopping on one foot or imitating hand gestures. Using children’s music DVDs or CDs can also allow practice of gross motor skills. “The Wiggles™”, a popular children’s singing group has several songs that encourage children to practice gross motor movements.

Steps to Developing an Ongoing System for Measuring Progress on CBAs

Creating a Visual Map of Learning Goals/Objectives

Creating a visual map of the curriculum goals and objectives is the first step in creating a system for collecting classroom data. Many teachers report feeling overwhelmed when first reviewing the seemingly large number of goals and objectives to be covered in a single CBA tool. Typically these measures span a wide age range, sometimes including goals and objectives from birth through age five or beyond. In most classrooms, the overall number of goals/objectives can be reduced to reflect the (chronological and develop-mental) ages being taught. A visual map helps to narrow the focus by identifying only the goals/objectives that will be covered within the program year for a specific classroom. In addition, a visual map can help teachers familiarize themselves with the specific goals and objectives that they will be measuring. In essence, the visual map is a snapshot of the curriculum for a year.

Using the AEPS Child Progress Record as a Visual Map

The AEPS Child Progress Record II (Bricker, Pretti-Frontczak, Johnson, & Straka, 2002) provides a succinct view of the goals and objectives to be taught and measured over the span of a child’s development. This form was designed to provide a visual display of current abilities, intervention targets and child progress all in one form.

Figure 1 shows the first page of the AEPS Child Progress Record II. To use this form to create a visual map, a highlighter is used to underline the arrows below each of the goals and objectives to be measured for the year. For teachers serving children in multi-age classrooms or for homogeneous classrooms of four-year-old children, this step may not be necessary (in those cases all goals and objectives would be highlighted). Teachers serving younger children may determine that not all the goals and objectives will be taught within a given school year. In those cases specific goals/objectives would be identified and highlighted with a marker and then be used as a reference point from which to plan learning activities, record group and individual progress, and analyze the overall effectiveness of the program.

Teachers using a CBA that does not provide a visual record for documenting child progress can create their own graphic display of their curriculum goals and objectives using the AEPS Child Progress Record format as a template. Teachers may want to expand on the AEPS display format to create a visual map of their own that incorporates goals from additional curricular materials (i.e., supplemental literacy or social skills curricula) and provides a visual alignment with the Kansas Early Learning Document (KSELD) Early Learning Standards (ELS). The publisher of the AEPS has created a visual alignment of the tool with the KSELD/ELS, available for download from AEPS Interactive.

If you use other curriculum materials, contact the publisher to ask if they have completed (or are willing to complete) an alignment with the KSELD/ELS. For additional information on curriculum alignment with the KSELD/ELS, visit KSDE.

- This section has a diagram from AEPS on Fine Motor Area and Gross Motor Area. To receive a digital copy, please email kskits@ku.edu.

Bricker, D., Pretti-Frontczak, Johnson, J. J., & Straka, E. (2002). Assessment, evaluation, and programming system for infants and children: Administration guide (Vol. 1, 2nd ed., pp. 284-285). Baltimore: Brookes. Adapted with permission

Reviewing Classroom Schedules/Routines to Embed Assessment Activities

Once the visual map has been created, the next step is to take a closer look at the classroom schedule, routines and activities and identify the specific learning goals and objectives to be assessed. The following are just a few examples of possible learning objectives from the AEPS that could be assessed within a typical preschool schedule:

- Arrival: Greeting, responding, interacting, dressing/undressing, sequencing

- Free Choice: Most skills, depending on the activity, e.g., engaging in cooperative, imaginary play, problem-solving, using language for different functions, initiating and responding to requests for social interaction, initiating and completing age-appropriate activities

- Circle Time: Group membership skills such as following rules, participation in a group, social communication, recalling events, counting

- Bathroom time: Personal hygiene, dressing/undressing, sequencing

- Snack: Social communication, eating with utensils, group participation, knowledge of self and others

- Transitions: Classroom rules, following directions, cooperation, recall, sequencing, one-to-one correspondence

- Outdoor: Gross motor skills, social interaction, follows rules/safety, dressing

- Small Group: Most skills, depending on the activity, e.g., using two hands to manipulate objects, cutting, writing, demonstrating understanding of concepts, phonological awareness, asking and answering questions that require reasoning, use of verbs, nouns, pronouns, descriptive words, word endings

- Dismissal: Dressing/undressing, sequencing, recall

The AEPS includes sets of assessment activities to help teachers assess individual children across a variety of settings, or to facilitate assessment of a group of children simultaneously. The activities are included in Appendix A of the Volume 2 Test: Birth to Three Years and Three to Six Years (Bricker, et al., 2002).

Teachers using different CBAs may find the AEPS assessment activities helpful in designing similar types of assessment activities based on their own CBA.

It is important to remember that while all learning activities serve a purpose, not all lend themselves to curriculum assessment. In general, the best activities for measuring progress are highly motivating, open-ended, elicit a variety of skills across a number of domains, and provide the “biggest bang for the buck” in terms of assessment. Illustrations of strategies for embedding skills assessment into popular learning centers are provided in the next section.

Learning, Practice, Mastery

Children need ample time to learn, practice, and master newly introduced skills or information. Teachers must keep this in mind when assessing mastery of new skills. We recommend that children attending a four or five day-a-week preschool program be given approximately three weeks from the time a new skills/information has been introduced before assessing for skill mastery. Within this three-week period, teachers will observe children provide scaffolding to support their learning and mastery. Not all children being assessed will exhibit mastery as the same time. Your assessment results, however, will provide the information needed to make appropriate instructional changes for groups and individual children.

Examples of Embedding Skills Assessment in Learning Center Areas

This section contains:

- Discrimination/Classification Skills

- Dramatic Play

- Block Area

- Art

- Gross Motor Area

- Fine Motor

- The Book Corner

- Application Activity

Discrimination/Classification Skills

Mrs. Smith wants to increase her students’ opportunities to practice the discrimination/ classification skills of color/shape recognition and pre-writing skills. She finds that many of her students spend a large amount of time building with large wooden blocks in the block area. Blocks provide many opportunities for shape recognition, but all of the blocks are the shade of natural wood. Mrs. Smith decides to add additional toys to the block area to expand discrimination/classification and fine motor opportunities. She adds a tub of small, colored wooden blocks of various shapes, zoo animals and a sign making kit. The sign making kit contains pre-cut colored shapes, assorted sizes of colored markers, tape, “Tinker Toys” for the bases of the signs and picture/word cards with frequently used signs and zoo animal names for the children to refer to.

The following photos and descriptions are examples of free choice activities and skills that can be measured during classroom experiences. It is important to note that all of the activities are open-ended and the skills measured are dependent on the developmental level of the group of children who are participating in the activity. Examples of target skills to be assessed are from the AEPS (Bricker, et al., 2002).

Dramatic Play

Skills to be measured might include:

- Cognitive F 1.2 Plans and acts out recognizable event, theme or storyline

- Cognitive F 1.1 Enacts roles or identities

- Social A 2.2 Maintains cooperative participation with others

- Social A 1.2 Establishes and maintains participation with others

Block Area

Non-traditional materials can be added to the block area to encourage pre-writing skills for students. Cognitive and fine motor skills are targeted in the skills to be measured for these students. However, the activity could be set up to encourage other skills. What other skills could you measure within this same activity?

Skills to be measured might include:

- Fine Motor A 2.1 Cuts out shapes with straight lines

- Fine Motor A 2 Cuts out shapes with curved lines

- Fine Motor B 1.1 Writes using three-finger grasp

- Fine Motor B 3.3 Copies three letters

- Cognitive C 2 Places objects in order according to length or size

Art

In this example, students are using a purchased “Spin Art” activity to make their own creations. Routines can be added to this favorite activity to encourage children to write their names on the back of their paper and choose a specific number of different colored markers to use as they take turns spinning the wheel.

Skills to be measured might include:

- Fine Motor B 1.1 Uses three-finger grasp to hold writing implement

- Cognitive A 1.1 Demonstrates understanding of eight different colors

- Cognitive G 1.2 Counts 3 objects

- Social A 1.3 Takes turns with others

Gross Motor Skills

Writing materials can be added to the bowling activity in the gross motor area. Dry erase markers and dry erase boards with number strips give children a way to keep score as they bowl.

Practice: What goals and objectives could be measured while these students play? To make the activity rich in opportunities, remember to select skills from across domains.

Fine Motor Skills

Collage materials make a wonderful activity in a fine motor area. Materials might include: scissors, magazine pictures, and pre-printed colored shapes.

Practice: What skills could be measured with the existing materials? What additional materials could be added to measure different skills? What skills could be measured with the addition of materials?

The Book Corner

The book area should contain books that are related to the current theme and other books that are familiar and favorites of the students.

Practice Think of at least four skills from at least two different domains that could be measured in this area.

Application Activity: The Vet’s Office

The following photographs depict a dramatic play center in a three to five year old preschool classroom. The “Vet’s Office” contains an area for the animals, (with each animal having its own box, labeled with a picture and print title), a book with the animal’s photograph on the front and blank pages of paper inside for documenting pet care, doctor’s kits for medical care, grooming tools, food and bowls for feeding, a cot for animal care and a reception desk with a variety of writing tools, clipboard, paper, appointment cards and telephone.

Practice Using your curriculum-based assessment as your guide, make a list of all of the skills that could be measured within this activity. Look across the developmental domains. Think about the range of student abilities that could be met within this same activity.

Collecting and Recording the Data

This section contains:

- Data Collection Forms

- Compiling the Data

- Organizing Your Data Collection System

Data Collection Forms

Teachers identify specific skills to be assessed and record them on data collection forms. Three types of data collection forms are discussed as a part of this packet:

- Large Group Data Collection

- Teacher Made Independent Activity Data Collection Form (Figure 1a)

- Teacher Made Independent Activity Data Collection Form Example (Figure 1b)

- Small Group Data Collection

- AEPS Assessment Activities with data collection forms available in Appendix A of Volume 2 Test (Bricker, et al., 2002)

- AEPSi Assessment Activities (With subscription or 30-day free trial, small group activities with data collection forms can be downloaded from AEPSI (Figure 2)

- Teacher Made Small Group Data Collection Form (Figure 3a)

- Teacher Made Small Group Data Collection Form Example (Figure 3b)

- Language samples

- Teacher Made Language Sample Form (Figure 4a)

- AEPS Social Communication Observation Form (Figure 4b).

The independent and small group sample data collection forms are “activity specific” rather than “domain specific”, allowing teachers to implement best practice in terms of teaching “the whole child”. The independent activity forms are used to record progress data for children as they participate in routine or self selected activities during the daily schedule. Specific learning goals/objectives to be assessed are selected by the teacher and recorded in the boxes on the left hand side of the form. As children progress through the curriculum, the teacher can update the goals and objectives on the form. Although sample assessment activities provided are specific to the AEPS, these forms could be adapted for use with any curriculum- linked assessment.

The AEPS Social Communication Observation Form is domain specific; conducted during ongoing activities it provides an organized way in which to collect a large number of language samples to assess specific social-communication skills within a variety of classroom activities.

For additional examples of data sheets for authentic, activity based instruction see also the DEC Recommended Practices Toolkit (DEC, 2006) module on Monitoring Children’s Learning.

Figure 1a: Independent Activity Data Collection Form (Blank)

Activity/Description:

| Data Collection Form | Goal 1) | (Goal 2) | (Goal 3) | (Goal 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student 1 | ||||

| Student 2 | ||||

| Student 3 | ||||

| Student 4 | ||||

| Student 5 | ||||

| Student 6 | ||||

| Student 7 | ||||

| Student 8 | ||||

| Student 9 | ||||

| Student 10 | ||||

| Student 11 | ||||

| Student 12 | ||||

| Student 13 |

Figure 1b: Independent Activity Data Collection Form (Example)

Activity/Description:

| Data Collection Form | Adaptive C 1.3 Unzips zipper | Cognitive C 1.1 Follows directions of 3 or more related steps that are routinely given | Social A 1.5 Responds to affective initiations from others | Social A 1.4 Initiates greetings to others who are familiar |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eli | ||||

| Brooke | ||||

| Trae | ||||

| Riley | ||||

| Wyatt | ||||

| Garrett | ||||

| Pete | ||||

| Kathy | ||||

| Ashley | ||||

| Brandi | ||||

| Haven | ||||

| Kylie | ||||

| Ben |

Helpful Idea: Organize Measurement by Day of Week

Teams may decide to further organize measurement activities by assigning a day of the week to specific routine activities. For example, Monday could be used to assess skills during the arrival activity. Tuesday could be used to assess skills during bathroom time, etc.

Figure 2: AEPSi

(30-day free trial available from AEPSi)

- This section has a checklist from AEPSi on Fine Motor Area and Gross Motor Area. To receive a digital copy, please email kskits@ku.edu.

Brookes. (2008). AEPSinteractive. Author. Reprinted with permission. Download form at AEPSi

Figure 3a: Small Group Data Collection Form (Blank)

The Small Group Data Collection Form is used when the teacher or other adult leads a small group of children (between 3-5 children) through a specific learning activity with the aim of addressing selected curricular objectives. Like the Independent Data Collection Form, specific learning goals/objectives are selected by the teacher and recorded in the boxes on the left hand side of the form.

Activity/Description:

| Data Collection Form | (Goal 1) | (Goal 2) | (Goal 3) | (Goal 4) | (Goal 5) | (Goal 6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student 1 | ||||||

| Student 2 | ||||||

| Student 3 | ||||||

| Student 4 | ||||||

| Student 5 |

Figure 3b: Small Group Data Collection Form (Example)

Activity/Description: Matching Middles/Oreo Shape Game

(Fisher Price/Use two sets if you only want to measure a limited number or shapes (i.e., circle)

| Data Collection Form | Cognitive A 1.2 Demonstrates understanding of five different shapes | Cognitive F 2.1 Maintains participation | Cognitive F 2.2 Conforms to game rules | Social B 2.1 Interacts appropriately with materials during small group activities | Social B 2.2 Responds appropriately to directions during small group activities | Social D 1.2 Selects activities and/or objects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student 1 | ||||||

| Student 2 | ||||||

| Student 3 | ||||||

| Student 4 | ||||||

| Student 5 |

Figure 4a: Language Sample Recording Form (Blank)

Child:

Date:

Teacher:

Begin Time:

End Time:

Activity:

Setting:

| Utterance | Comment |

|---|---|

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | |

| 14 | |

| 15 |

Summary Notes:

Figure 4b: Social-Communication Observation Form (SCOF) (Blank form)

Child's name:

Observer/Activity:

Others Present:

Date:

Time (start):

Time (stop):

Total Time:

Record Child Utterances Word for Word u=unintelligible word (u) = unintelligible phrase | Context | Function Initiation | Function Response to Comment | Function Response to Question | Function Imitation | Function Unrelated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | ||||||

| 3 | ||||||

| 4 | ||||||

| 5 | ||||||

| 6 | ||||||

| 7 | ||||||

| 8 |

Users may need to make multiple copies of the form to accommodate an adequate language sample for individual children.

Adapted from Bricker, D., Pretti-Frontczak, Johnson, J. J., & Straka, E. (2002). Assessment, evaluation, and programming system for infants and children: Administration guide (Vol. 1, 2nd ed., p. 207). Baltimore: Brookes. Reprinted with permission

To help make data collection manageable, the teacher may wish to set up a rotating system for collecting and recording language samples. The schedule could be taped on the back of a clipboard that contains blank copies of the SCOF for the teacher or other support person to use as a reference when recording data (see example below).

AEPS SCOF Data Collection Schedule

- Monday

- Ben

- Kylie

- Haven

- Tuesday

- Brandon

- Ashley

- Kody

- Wednesday

- Pete

- Garrett

- Wyatt

- Thursday

- Riley

- Trae

- Brooke

Compiling the Data

This section outlines a sample process developed by the first author, an early childhood special education teacher, for recording and summarizing data collected in whole class, small group, and individual settings to monitor class performance on a curriculum-based assessment [in this example, the Assessment of Education Program Support (AEPS)].

The collection of data on an ongoing basis is a foundational practice central to quality services for young children. Data collection on a scheduled and frequent basis is important for a variety of reasons. These include measuring children’s progress referenced to the curriculum and/or standards, making decisions regarding instruction and modification of instructional strategies, and evaluation of the overall early childhood program and its impact on the learning and development of children.

Data collection does not have to be a cumbersome task and should be designed to answer specific questions related to a child’s progress within the curriculum and desired developmental outcomes. Data collection should be targeted across the child’s day and across settings, activities, and groups. Analysis may well involve examining quality of response as well as quantity of response. Simple data sheets can facilitate collection of information. Both the previous section and the following pages provide ideas for both teacher made and commercially available forms.

Figure 5: Whole Class Data

In the following example the AEPS Child Progress Record is used to chart the targeted curriculum learning goals/objectives for the entire class, while keeping track of data collection dates and overall progress towards accomplishing those goals/objectives. Regularly reviewing this information provides opportunities to make instructional changes within the curriculum, as needed. Note the following teacher adaptations:

- All targeted goals are underlined with a highlighter.

- The month and day that each set of data is collected is marked within the goal and objective arrow (i.e., 9/25).

- When the entire class has completed a goal or objective, the arrow is filled in with a highlighter. Different colors of highlighters can be used to depict the different quarters of the school year.

- This section has a diagram from AEPS on Fine Motor Area and Gross Motor Area. To receive a digital copy, please email kskits@ku.edu.

Figure 6: Individual Data

In this example the AEPS Child Progress Record is used to monitor each student’s progress so that instructional decisions can be made in a timely manner specific to the needs of the individual child.

- Child’s name and school year are placed in the upper left corner (i.e., Ben, 20062007).

- Class goals/objectives for the year are underlined with a highlighter.

- “+” or “–“ indicate individual student performance on the goal/objective arrow using data from collection sheets.

- Additional notes are included as needed to inform instructional decision making (i.e., Objective 1.1 R – or R + indicates right handed inappropriate grasp, right handed appropriate grasp).

- When the student has mastered the goal or objective, the arrow is filled in with a highlighter.

- This section has a diagram from AEPS on Fine Motor Area and Gross Motor Area. To receive a digital copy, please email kskits@ku.edu.

Figure 7: Whole Class Data

In this example, the AEPS Child Progress Record is used to document in a visual manner the students who have mastered goals or objectives to eliminate unnecessary data collection. The first and last initials are recorded within appropriate arrows for those students who have mastered the goal or objective. Data will not be collected for these students in future activities. When all students have mastered a specific goal or objective, the arrow is shaded with a highlighter.

- This section has a diagram from AEPS on Fine Motor Area and Gross Motor Area. To receive a digital copy, please email kskits@ku.edu.

Figure 8: Small Groups/Centers Data

This form is an example of a teacher-made weekly data collection form.

- Student names are listed under numbers at the bottom of the data collection sheet.

- Goals or objectives that were measured are listed in the left-hand vertical boxes.

- Data collected for each child is marked with the date of collection (i.e., 1/4) and “+” or “-“ for the skill demonstrated.

- Shaded boxes indicate that the student has already mastered the goal or objective, and that no data is needed. • Materials used in the activity are listed at the bottom of the page for activity set-up and future reference.

- This section has a Tactile Table. To receive a digital copy, please email kskits@ku.edu.

Figure 9: An Expanded List of Concepts Assessed by the AEPS

In some cases a published curriculum may not be specific about concepts to be taught, making ongoing assessment difficult. The following form created in an early edition of the AEPS may be useful in helping teachers to target and monitor cognitive goals and objectives that may include numerous concepts. A teacher might make a copy of the form for each student to be kept with their Child Progress Record. When a student has met the criteria for mastery of a goal/objective, the appropriate arrow is filled in and the date is marked on the Child Progress Record.

| Cognitive A 1.1 COLORS (8) | Cognitive A 1.2 SHAPES (5) | Cognitive A 1.3 SIZE (6) | Cognitive A 2.1 QUALITATIVE (10) | Cognitive A 2.2 QUANTITATIVE (8) | Cognitive A 3.1 SPATIAL RELATIONS (12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cognitive A 3.2 TEMPORAL RELATIONS (7) | Cognitive G 1.2 COUNTS 3 OBJECTS | Cognitive G 1.1 COUNTS AT LEAST 10 OBJECTS | Cognitive G 1 COUNTS AT LEAST 20 OBJECTS | Cognitive G 2.1 LABELS PRINTED NUMERALS TO 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Adapted from Early Intervention Program. (2000, July). AEPS measurement for three to six years, cognitive domain: Strand B: Demonstrates understanding of concepts (draft). Eugene, OR: University of Oregon.

Organizing Your Data Collection System

For data collection to be efficient and ongoing, it must be integrated into the routines of the classroom. The following practices were developed for use in an inclusive preschool classroom with 20 or more students.

Teacher Tips for Developing a Data Collection System

- Prepare your data collection sheets for the week in advance.

- Highlight the activities that you have targeted for data collection on your weekly lesson plan. This allows all staff members to review where data will be collected, at a glance.

- Use clipboards for data collection sheets. Consider marking the back of the clipboard with the area the data will be collected (i.e., Dramatic Play, Arrival, Small Group).

- Pick a day of the week to record collected data on the individual student progress records. The data cannot drive your instruction unless it is recorded and reviewed.

- Make a set of notebooks to store data. One notebook can be utilized for individual student progress records, another for completed data collection sheets, and a final notebook to store copies of frequently used data collection sheets to be copied and reused at a later date.

Using the Data

This section contains:

- Organizing Data to Create a Visual Display

- Interpreting Data to Make Instructional Decisions

- Summary

Organizing Data to Create a Visual Display

Collecting and recording progress data on skills embedded into ongoing activities and routines is the first step toward becoming a data-based decision maker. Researchers suggest organizing data on target goals or objectives into a graphic displays that illustrate performance over time, promotes systematic use of the data for instructional decision making (Hojnoski, et al., 2009b). Graphic representation of data has been identified as a critical component of most problem-solving models, including response to intervention models such as Recognition and Response (Coleman, Buysse, & Neitse, 2006), an early intervening model for early childhood. Data-based decision making is likewise at the heart of the Kansas Multi-Tier System of Supports (MTSS), developed to support the academic and behavioral needs of all learners in pre-K through grade 12 public education programs in the state Kansas MTSS and Alignment.

Graphs and visual displays are inherent in many CBAs. Online data recording and monitoring systems with graphing features, such as the AEPSi, are becoming more widely available. However, if the CBA you are using currently does not include graphic displays or electronic data systems, you can create your own graphs with software programs such as Microsoft Excel or with paper and pencil (Hojnoski, 2009b).

Interpreting Data to Make Instructional Decisions

As discussed previously, a fundamental purpose of assessment is to establish initial and present levels of performance regarding important skills from which a baseline can be established and skill acquisition can be measured. Ultimately the information is used to inform instructional decision making, and to adapt educational plans accordingly. When analyzing curriculum based assessment data, an early childhood team is able to determine if the instructional program is having a positive effect on the class and for individual children. If the program is not having the desired effect, the team will need to discuss potential reasons why specific objectives are not being mastered (by groups or individuals).

Hojnoski, et al. (2009b) advise that prior to deciding how to respond to data that suggests insufficient progress, teams ask themselves a series of questions, including:

- Have adequate opportunities for instruction and practice been provided as intended?

- Is the targeted skill or behavior of concern one that may take more time to change?

- Are the instructional opportunities that have been provided sufficiently intense enough to bring about change?

Your team may think of other instructional variables to be considered. At this point it may be necessary to collect additional observational or assessment information to identify specific modifications, adaptations, or assistance that might be needed to improve student performance. Changes to the environment, curriculum, materials, time, schedule, and/or teaching methods may need to be considered in relation to the information gained through assessment activities and the identified needs of each child.

The following vignette illustrates how adaptations to daily activities provided the opportunity to collect and utilize ongoing assessment data to drive future instruction in a preschool classroom.

After Mrs. Smith and her early childhood team reviewed the data collected for a three-week period, they identified several students who had not achieved targeted skills in the areas of fine motor and pre-writing. Therefore the team decided to modify a highly motivating upcoming learning activity planned for the dramatic play area, the “Car Wash/Fix It Shop”, to include fine motor and pre-writing tasks.

Materials were added to the activity to encourage fine motor and pre-writing skills: a table and chairs (to provide a surface for writing), a cash register and tickets for charging of services (for children to write out specific amounts due, and provide “payment”), vocabulary cards with theme related pictures and words (to encourage writing/modeling), and a variety of markers and colored pencils. An adult was stationed in the center to model writing and encourage participation and practice.

By the end of the week, two of the targeted students had exhibited significant progress on functional prewriting tasks, and it was decided that the third student would benefit from opportunities for more individualized instruction in this area.

Visual displays and graphing information can also be used to communicate with family members, sharing current information regarding targeted goals and objectives and providing a concrete representation of their child’s progress over time. While the first conference with families in which progress data is shared may take more time, subsequent conferences take less time as you will only need to review the newly accomplished goals/objectives and discuss the child’s next steps or areas of concerns. Your team’s observational and anecdotal notes, formal test summaries, and current information from the family should also contribute to your authentic assessment results.

Summary

As mentioned earlier, the decision to require the use of information from an approved curriculum based assessment in reporting child progress on Early Childhood Outcomes in Kansas largely was based on the understanding that CBA is an effective way to gather information that can be used for program planning and monitoring child progress in the general early childhood curriculum. It was hoped that practitioners would find CBA data useful beyond determining Child Outcome Summary Form (COSF) ratings at program entry and exit.

As we have demonstrated, CBA tools can provide a way to document continuous progress and mastery of specific curricular goals and objectives. This mastery measurement approach provides educators with the opportunity to identify explicit gains for individual learners, as well as compare those gains with the performance of the entire classroom. CBA results can then be used to evaluate the effectiveness of the overall curriculum (e.g. average performance of children within domains), and shared with family members, service providers, boards of directors or others who may support the ongoing needs of the preschool program.

This packet was designed to illustrate ways that curriculum based assessment information can be used to improve teaching and learning in a preschool classroom. We hope the information, examples and resources provided in this packet will assist practitioners in the creation of a system for ongoing assessment during daily activities and routines that will make the task of collecting, recording, interpreting, and using CBA data less daunting and more worthwhile.

Interactive Activity

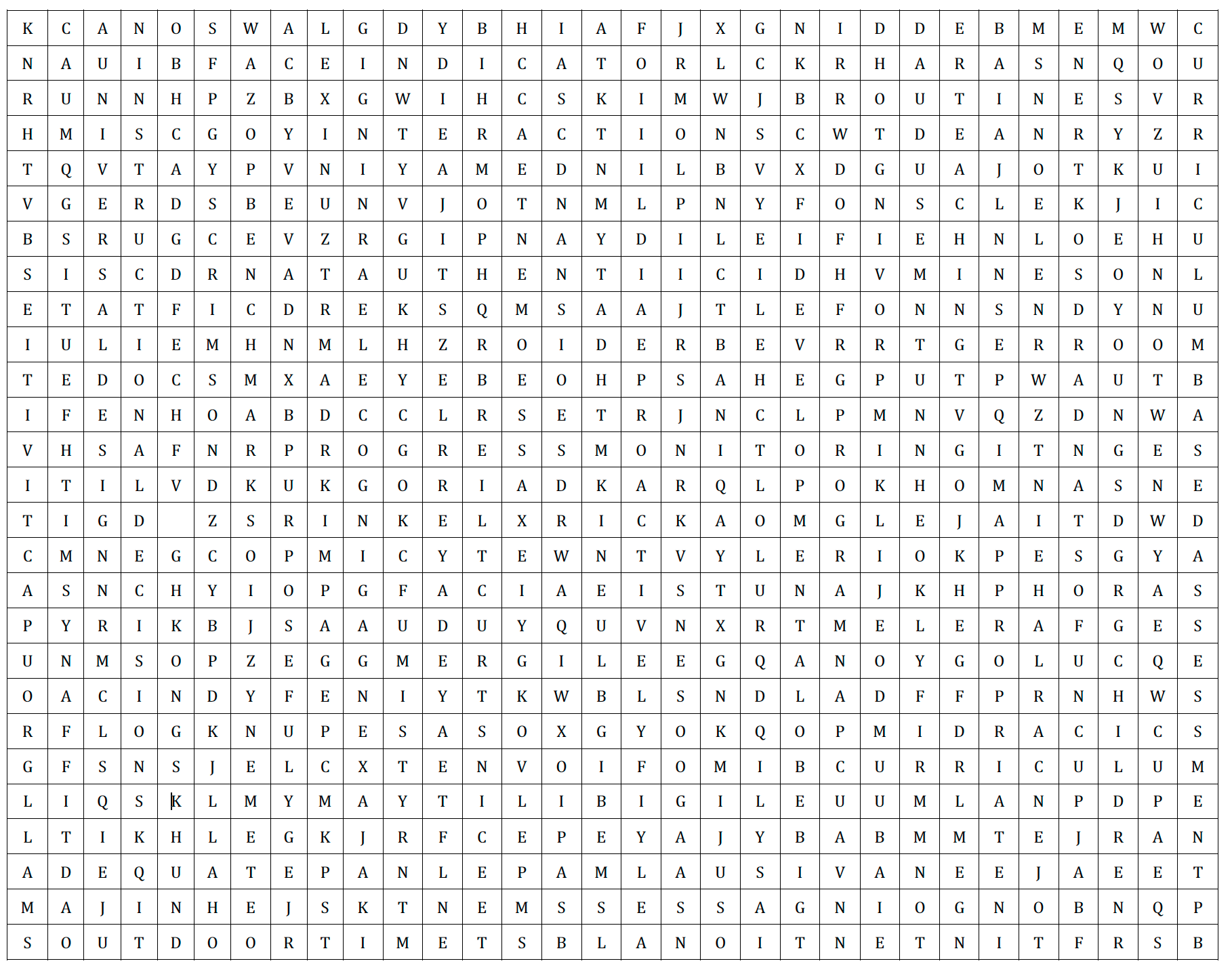

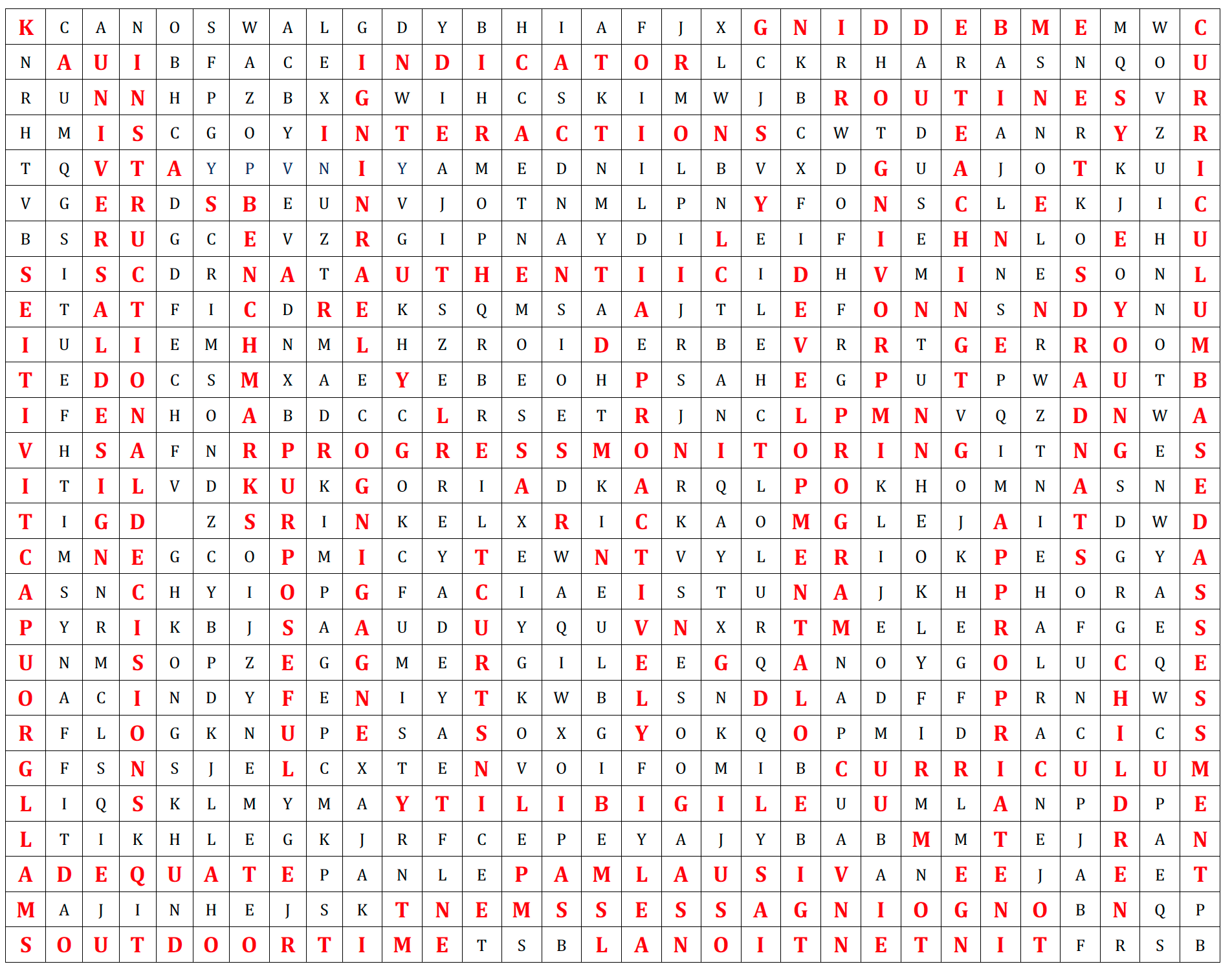

Once you have completed this technical assistance packet, you should be able to complete each of these statements. But don’t worry. We’ve included the answer key at the end. If you’d like an extra challenge, complete the word search puzzle, too.

- Proactively planning authentic assessment provides a process for reorganizing curriculum based assessment items according to daily ___________ of young children and results in a form for recording simultaneous systematic observations of multiple children (Cook, 2008).

- The intent of ___________ assessment is to create a link between children’s abilities and appropriate interventions within the context of familiar surroundings (Meisels, 1997).

- A ___________ is a series of planned, systematic learning experiences organized around a particular philosophy of learning, includes a scope and sequence of learning goals, and provides a predetermined order in which individual skills should be taught in a developmentally appropriate manner.

- ________________ ________________ is an unstructured period when children engage in a variety of gross/fine motor, and social activities that can be used to practice specific skills and/or allow for the collection of assessment data.

- Ultimately, assessment information is used to make good _______________ _______________ that is aimed at improving outcomes for individuals as well as groups of children.

- ___________ are increments of an early learning standard that are used to gauge progress.

- Designing and scheduling assessment activities linked to the early learning standards and curriculum ___________ promotes the ongoing collection of information in a way is less intrusive and more authentic.

- If, after reviewing progress monitoring data, it is believed that the learning goals continue to be appropriate, then changes in the daily schedule, ___________ strategies, styles of interactions, interest area arrangements, materials, or the design and implementation of small group work may be what is required.

- A developmentally appropriate curriculum provides direction for organizing and planning teaching through ___________ activities, identification of specific materials, environmental arrangement, and utilization of specific intervention strategies.

- When reviewing the collected assessment data it is important to determine if the instructional opportunities provided have been sufficiently ___________ enough to bring about change.

- The KSELD-ELS was created by a diverse group of early childhood stakeholders using current research and evidence regarding early___________.

- Early learning activities designed for young children should be proactively planned, ___________, and designed to be playful, motivating, and meaningful.

- ___________ evaluation provides systematic assessment of the effects of the broad overall system with the intention of examining the need for additional resources, realignment of services, professional development, and provides evidence of accountability.

- School districts and infant toddler networks serving young children with disabilities are required to use a ________________ ________________ ________________ in the Early Childhood Outcomes rating process.

- It is imperative that early childhood professionals continually engage in assessment for the purpose of ___________ teaching as well as learning.

- Early childhood professionals cannot be ___________ about helping children to progress unless they know where each child is with respect to learning goals.

- ___________ assessments within and across day to day activities allows the observer to gather information across various domains and skills as children perform routine tasks (Dunlap, 1997).

- At a minimum, early childhood professionals should conduct an ongoing (formative) review of the child’s progress at least every ___________ days in order to modify instructional strategies appropriately.

- One of the most difficult tasks in designing a system for monitoring progress is choosing tools and strategies that are not only appropriate for young ___________ but that will also provide meaningful and useful information.

- A developmentally ___________ curriculum should be aligned with the Kansas Early Learning Document-Early Learning Standards (KSELD-ELS), and implemented with fidelity.

- The term ________________ ________________ is used to describe the proactive planning and creation of learning opportunities that allow all children to access, participate in and benefit from the general education curriculum as required in the IDEA amendments of 2004, increasing the likelihood of positive outcomes for all children (DEC, 2007).

- Curriculum based assessment is a form of criterion-referenced measurement, which utilizes curriculum objectives to identify targets to ___________ assess, and from which performance can be monitored over time. (Bagnato, 2007).

- Assessment information collected by early childhood professionals should be used to plan curricular activities, learning experiences, and in moment-to-moment ___________ with children.

- An ___________ is an example behavior, piece of knowledge, or skill that a child might demonstrate at different levels of development in order to meet a specified benchmark.

- Before deciding how to respond to the data that have been collected, the teacher must first identify if ___________ opportunities for instruction and practice have been provided as intended.

- ___________ is a term describing a determination based on assessment information and evaluation procedures used to identify if a child meets certain requirements that entitle him/her for specific services (e.g. early intervention/special education).

- Ongoing assessment methods used to track performance on specific targets or skills are often referred to as ________________ ________________.

- A ___________ screening is conducted to determine if a need for a more comprehensive assessment and evaluation is needed.

- The ______________ ______________ ______________ ______________ includes early learning standards that are appropriate for young children birth through age five.

- ________________ ________________ refers to the frequent and systematic collection and analysis of data to determine child progress and to make instructional decisions that promote the achievement.

- Intentional learning opportunities should be proactively designed to be developmentally and individually appropriate, child centered, actively ___________ and challenging (Sandall, et al, 2005).