Creating Environments to Support Positive Behavior

Feel free to print and/or copy any original materials contained in this packet. KITS has purchased the right to reproduce any copyrighted material included in this packet. Any additional duplication should adhere to appropriate copyright law.

The example organizations, people, places, and events depicted herein are fictitious. No association with any real organization, person, places, or events is intended or should be inferred.

Compiled by Susan L. Jack M.Ed. and David P. Lindeman, Ph.D.

March 2012

Adapted from the technical assistance packet: Environmental Support for Positive Behavior Management (1998)

Kansas Inservice Training System

Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities

Adapted for accessibility and transferred to new website October 2022

Kansas Inservice Training System is supported though Part C, IDEA Funds from the Kansas Department of Health and Environment.

The University of Kansas is and Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action Employer and does not discriminate in its programs and activities. Federal and state legislation prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, religion, color, national origin, ancestry, sex, age, disability, and veteran status. In addition, University policies prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, marital status, and parental status.

Letter from the Director

March 2012

Dear Colleague,

As educators, we must be prepared to provide a positive learning environment to support the positive social/emotional development, to prevent problematic behaviors, and to be prepared to respond should problems occur. Children with disruptive or challenging behavior are a concern to all who interact with that child or have responsibility for that child.

The understanding of the importance of social/emotional development has greatly expanded in recent years. Also, the US Department of Education has identified positive social/emotional development as one of three outcomes for children. The information in this packet is based on the research and evidence-based practices in the field of early childhood education. Please disseminate as appropriate.

We hope that you will find that the packet contains helpful information. After you have examined the packet, please complete the evaluation found at the end of this packet. Thank you for your interest and your efforts toward the development of quality services and programs for young children and their families.

Sincerely,

David P. Lindeman, Ph.D.

KITS Director

Introduction to Creating Environments to Support Positive Behavior

Creating supportive environments provide structure in the classroom, and promote the development of children’s social and emotional behavior and learning. Effective classroom environmental support strategies provide information to children about what is expected in the classroom at any given time, and help them move independently through routines and activities. These strategies include: consistent and structured routines, clear expectations, planned transitions, and providing group and play activities to promote child engagement and foster friendships.

Arranging a classroom environment to manage and support positive social/emotional development and appropriate behavior is a proactive, rather than reactive, approach to teaching children social skills while reducing the likelihood of problem behaviors. The environmental support strategies discussed in this packet are ones that will help develop a positive classroom environment and will prevent most problems before they occur. The article by McEvoy, Fox, and Rosenberg (1991) highlights many of the strategies discussed in this packet and gives useful suggestions for organizing preschool environments.

Nurturing and Responsive Relationships

The bottom tier of the Pyramid Model identifies nurturing and responsive relationships between children and their caregivers and teachers as a foundation to positive social/emotional development. When adults and children are connected through a strong relationship, they are more likely to develop and maintain positive interactions and foster trust. In addition, children are more likely to develop a sense of self-confidence and safety that will reduce the likelihood of problem behavior (Fox, Dunlap, Hemmeter, Joseph & Strain, 2003).

For most young children, adult attention is one of the most influential reinforcers available. Young children will often go to great lengths to get adult attention, in whatever form they can obtain. The proactive approach is to provide positive attention to children on a regular basis, rather than to react when they misbehave by providing negative attention.

Positive adult attention can affect child behaviors in a number of ways. It can increase child engagement, increase the amount of positive teacher-child interactions, and decrease the frequency of child disruptive behaviors. Positive attention can be in the form of pleasant teacher-child interactions, physical contact, and physical proximity between teacher and child.

One simple way to provide positive attention is to use verbal praise when children engage in appropriate behavior. Verbal praise is one of the most important techniques of teaching and can be a powerful reinforcer for child behavior. But praise needs to be something more than the same few phrases repeated over and over. Praise should be given freely, sincerely, and accompanying other reinforcers. It should also be used to support effort and improvement. There are several advantages to using verbal praise: 1) it is transportable - it can be given most any place and at most times, 2) it is economical - it requires small effort on behalf of the teacher, 3) it can be trained - anyone can be taught to use praise effectively, and 4) it can gain power over time when paired with other types of reinforcers. With these considerations in mind, the use of verbal praise can be a valuable tool in establishing and maintaining positive behavior in the classroom. See the following table to find 50 Ways to Praise and Encourage a Child.

Another way to use positive adult attention is with adult proximity and teacher movement in the classroom. By rotating attention among children on a regular basis, teachers and aides can influence children’s interactions with others, improve their attention to tasks, and decrease the likelihood that children will misbehave. The first step in planning a movement strategy is to determine the current movement patterns by the adults in the classroom. This could be accomplished by videotaping segments of classroom activity, or asking a peer or supervisor to observe and monitor movement patterns. It could also be assessed by placing pieces of paper about the classroom and having the teacher or aide mark the papers each time they pass.

Once a typical movement pattern is assessed, one could make modifications as appropriate or needed. Modifications could be made by drawing a map of the current layout of the classroom and noting areas that would hinder movement. The next step would be rearranging classroom layout to make movement easier and provide access to individual children, and dividing classroom into zones with paraprofessionals to cover all areas of the classroom effectively. Planned physical movement and the use of adult proximity is a simple strategy to use for managing child behavior. It involves developing a systematic plan for adults to move about the classroom and to be aware of how adult proximity can have influence over child behavior without additional prompting or engaging the child in any way.

The Adult Attention and Proximity Checklist in this section can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of the way adult attention and proximity is used in the classroom. For each item, answer “yes” or “no”; consider a “no” answer as an indication that there could be room for improvement. Use the Action column to write down some ways you could make these improvements or areas in which you need further assistance.

50+ Ways to Praise and Encourage a Child

- Wow!

- Way to Go

- Super

- You’re Special

- Outstanding

- Excellent

- Great!

- Good for You

- Well Done

- Remarkable

- I Knew You Could!

- I’m Proud of You

- Fantastic

- Nice Work

- Looking Good

- Now You’ve Got it

- You’re Incredible

- Bravo

- You’re Catching On

- Hurray for You

- You’re on Target

- You’re Smart

- Good Job

- Hot Dog

- Dynamite

- You’re Beautiful

- You’re Unique

- Nothing Can Stop You Now

- Much Better

- I Like You

- I Like What You Do

- I’m Impressed

- You’re Clever

- You’re a Winner

- Spectacular

- You’re Precious

- You’re Terrific

- Atta Boy

- Atta Girl

- Congratulations

- Hip, Hip, Hooray!

- I Appreciate Your Help

- You’re Getting Better

- I Trust You

- You’re Very Creative

- You Are Fun

- You Did Good

- I Like How You’re Growing

- I Enjoy You

- You Tried Hard

- You Are So Thoughtful

- You’re Important

- You’re a Treasure

- You Are Wonderful

- Awesome

- You Made My Day

- I’m Glad You’re My Kid

- Thanks for Being You

- I Love You! ALSO: A Pat on the Back

- A Big Hug

- A Kiss

- A Thumbs Up Sign

- A Warm Smile

Excerpted from The Winning Family, copyright 1993 by Dr. Louise Hart. Reprinted by permission of Celestial Arts P.O. Box 7123, Berkeley, CA, 94707

Adult Attention and Proximity Checklist

| Do you use adult attention and proximity effectively? | Yes | No | Plan of Action/Resources Needed |

|---|---|---|---|

Do you provide positive attention to children on a regular basis? | |||

Do you have a systematic class-wide reinforcement system? | |||

Do you use some form of tokens (e.g., stickers, points, checks) in your reinforcement system? | |||

Do you use a variety of precise statements throughout the day? | |||

Do you have a planned way of moving about your classroom? | |||

Do you place students close to you to aid in your ability to control their behavior? | |||

Have you designed a plan for movement with your assistant or paraprofessional? | |||

Do you have zones in the classroom that you and your assistant cover? | |||

Do you monitor your movement patterns? |

Adapted from Jack, S. L., et al (1996). An analysis of the relationship of teachers’ reported use of classroom management strategies on types of classroom interactions. Journal of Behavioral Education, 6, 67-87.

Physical and Programmatic Arrangement

The physical arrangement and programmatic structure of a classroom are pivotal features in developing an environment that supports learning and promotes positive child behavior. Children learn through active engagement and interaction with the social (e.g., peers, adults) and nonsocial (e.g., schedule, materials, activities) components of their environment (McEvoy, Fox, & Rosenberg, 1991). These features of the environment must be clearly designed to support teacher directed instruction as well as child-directed activities. Curricula should foster learning activities initiated by children, promote engagement with learning materials in the environment, and support identified and desired learning outcomes for the class as a whole and for each child. With effective planning and implementation, environmental features can provide the necessary cues for children as to what behavior(s) are expected and what activities are to occur in a given physical area of the classroom and at a given time. Effective teaching should also reflect developmentally appropriate and culturally relevant practices.

Considerations for the physical arrangement of the classroom include the layout of the physical space, placement of the furniture, equipment, toys and materials, and personal items in such a way to maximize the utility of that space. By focusing on these physical characteristics, opportunities for learning will be maximized while the potential for problem behavior will be minimized. Factors that will need to be considered regarding the physical arrangement are further determined by a number of parameters including age and number of children in a classroom, the types of planned activities to occur within the classroom, and special needs or accommodations required by the children in that classroom.

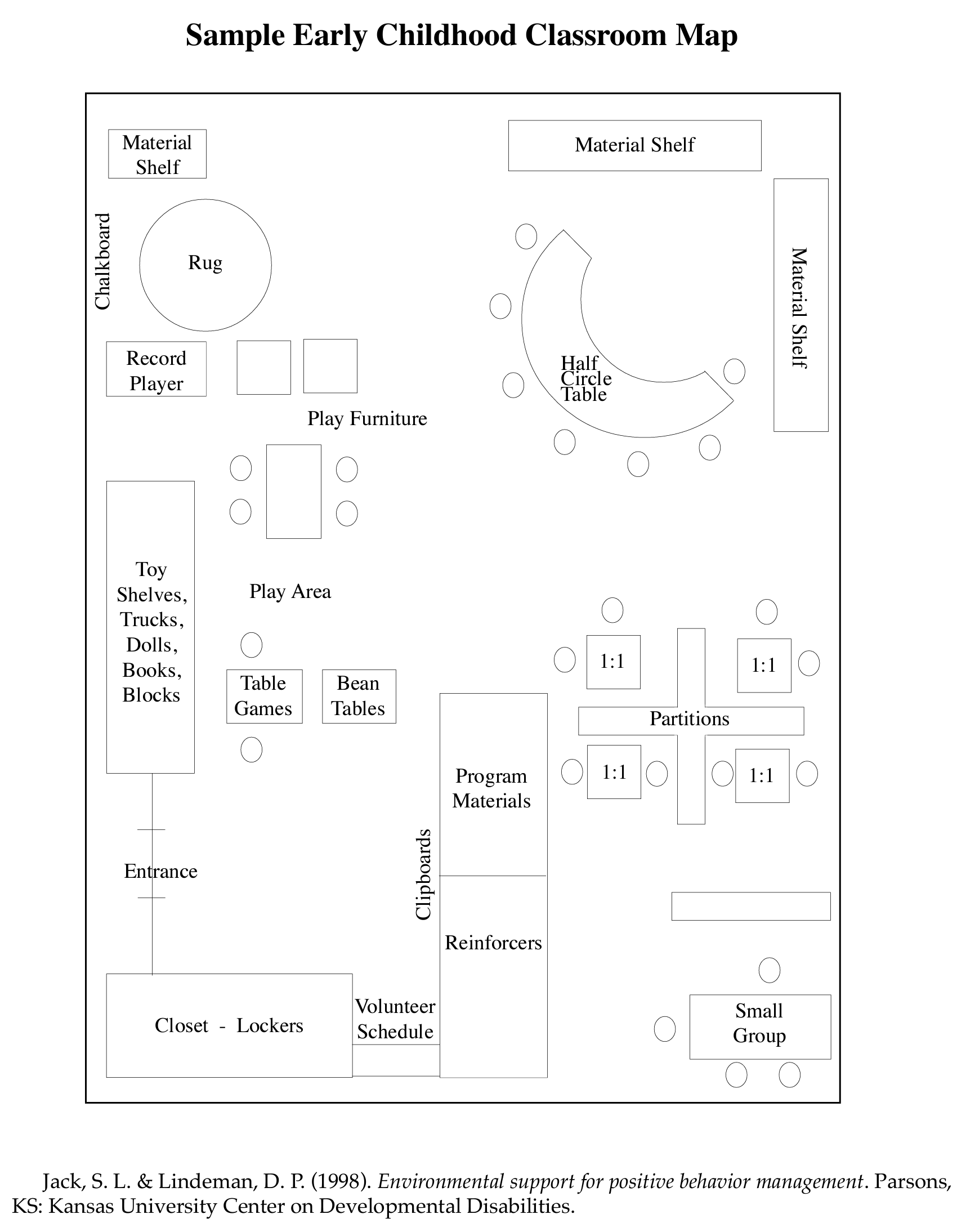

Classrooms should be physically arranged to provide specific and well-defined areas. The purpose of a planned physical arrangement is to support efficient traffic patterns and to divide the classroom into areas clearly designed for structured activities (e.g., small group, individual activities) or less structured activities (e.g., free time, dramatic play). While the utilization of furniture may be used to define these areas, these barriers should not prohibit communication with or visual observation of all children. The following Sample Early Childhood Map provides an example of a well-designed classroom.

Each designated area should support the activity for which it was designed while providing sufficient and appropriate space for children. For example, an area designed to promote social interaction between children will be smaller than an area designed to promote large muscle activity. The materials in the area should also support the activity. If social interaction is a desired outcome for an area, the staff will need to consider the number and types of toys in the play area. Research has shown that the selection and placement of toys can foster or impede social interaction between children (Bambara, Spiegel-McGill, Shores, & Fox, 1984; Elmore & Vail, 2011; Hendrickson, Strain, Trembley, & Shores, 1981; Ivory & McCollum, 1999). In this example, limiting some toys in the play area may foster cooperative play or sharing, thus supporting social interaction. On the other hand, children may have difficulty sharing some toys. This challenge could be solved by providing duplicate toys or by developing specific intervention strategies to address positive social interaction. This intervention or planning will be determined by the teacher and the designed purpose of the area. Structuring play and fostering interactions between children should also be tailored to the developmental needs of all of the children in a classroom.

Activities that will be conducted within each area of the classroom are another consideration in a well-designed classroom. One would not want to place a quiet reading/listening area next to the boisterous block area. Additionally, the placement of materials on shelves will need to be balanced with the instructional intent of those materials. If the intent is to support the children in self-initiating play with the materials, then they will need to be within easy reach of those children. However, if a planned instructional tactic involves children requesting certain materials, those materials should be placed in sight of the children while out of reach. This in turn will facilitate the children requesting or indicating their desire for those materials.

Zoning:

Promoting active engagement in the classroom environment is aided by visual cues posted about the classroom and by the way adults move around, shifting their attention and support among children and across activities. Visual cues, whether they are line drawing, photographs, or object placement, provide children with the guidance they need to properly engage in an activity, or complete a task independently. For example, a buddy chart may describe how to invite a friend to play, or a hand washing chart pictures the steps to washing hands. Visit Head Start Inclusion for teacher tools for classroom visual supports.

Adult movement in the classroom is a simple, yet effective way to promote child engagement and prevent problem behaviors. One way to think about it is “zone defense” where adults are located strategically in the classroom to assist with difficult routines, such as transitions or bathroom breaks. They can also be strategic in being available or in proximity to children during activities in which children may have more social emotional challenges. For example, an assistant teacher may remain near the dress-up area during center time to assist children with deciding what or how to pretend play. An additional tool for planning “zone defense” might be to revisit the Sample Classroom Map and plan out adult location and proximity during key routines or activities across the day.

The Physical and Programmatic Arrangement Checklist in this section can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of the way the physical arrangement and programming is used in the classroom. For each item, answer “yes” or “no”; consider a “no” answer as an indication that there could be room for improvement. Use the Action column to write down some ways you could make these improvements or areas in which you need further assistance.

Jack, S. L. & Lindeman, D. P. (1998). Environmental support for positive behavior management. Parsons, KS: Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities.

Physical and Programmatic Arrangement Checklist (BLANK)

| Things to consider | Yes | No | Comment/Suggestions |

|---|---|---|---|

Are most play areas large enough for social and parallel play? | |||

Is the environment arranged so that areas and tables are physically accessible by adults and children providing enough entry room, sturdy chairs, and enough floor room? | |||

Does placement of furniture facilitate movement from area to area (e.g. space for wheelchair) while at the same time create distinct areas? | |||

Are chairs or mats available for use for seating or group times? | |||

Are carpet squares or mats stored near group/circle time area? | |||

Are the boundaries visibly clear for different activity areas? | |||

Are materials provided to keep toys and equipment in a certain space when they are being used? | |||

Is there plenty of room for each child during table activities? | |||

Does each child have their own “working space”? | |||

Are “cues” (i.e., photos, pictures, outlines) placed on storage areas to promote using and putting away materials? | |||

Are materials on open, low shelves when children can help themselves? |

Adapted from Supporting Teams Providing Appropriate Inclusionary Preschool Practices in Rural States (STAIRS), Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities, Parsons, KS

Teaching Rules and Expectations

Another component of environmental supportive strategies is the explicit use of classroom rules and expectations. By clearly defining the expectations of appropriate child behavior and by establishing the relationship between behavior and its consequences children are better able to understand what is expected and how to treat one another. Clear expectations also help the teacher identify which child behaviors should be positively reinforced.

When universal expectations are developed within an early childhood program, children are more likely to receive clear and consistent messages about how to treat others, and what social behaviors are acceptable in the program. Staff are able to give feedback about children’s behaviors across activities and settings in terms that children are able to understand. Expectations will apply to a general set of social behaviors that may be further defined or narrowed according to different rules in different settings.

For example, “Be Safe” may be defined differently on the bus, on the playground, or in the classroom:

Bus: “Wear your seatbelt.”

Playground: “Stay inside the fence.”

Classroom: “Use walking feet.”

Under this umbrella of universal expectations, setting specific rules take on greater meaning and provide the context for positive feedback and recognition when children are meeting expectations.

The development of classroom rules involves a few simple steps. Specific behaviors should be identified in a written rule list. Rules should be limited to a small number, such as three to five. Having long lists of rules may confuse children about what is expected, and keeping the list simple will highlight the behaviors that are most important in the classroom. Rules should be phrased in the positive (to do), rather than in the negative (don’t do). Simply telling children not to run does not specify an alternative behavior. A better option is to specify a behavior (i.e., walking feet) that can be substituted for an undesirable behavior (i.e., running), which would provide the children with an opportunity to be reinforced. Children should also be provided with an observable definition of the desired behavior. Again, the purpose is to provide clarity about what it is they are supposed to do, and under what circumstances. Another benefit to providing observable definitions of behavior is that anyone else (e.g., substitute teacher, volunteers) will also be able to implement and enforce the rules if the primary teacher is absent. Posting the rules in a prominent place further enhances this point, by providing children and other staff with a visual cue about the relationship between classroom behavior and its consequences.

Algozzine & Ysseldyke (1992) suggest strategies to implement a system of classroom rules. The first strategy is to communicate the rules to children. This includes posting the rules to minimize misunderstandings, role-playing rule situations by using examples of rule following and infractions, teaching children your signal for rule infractions, and reviewing rules frequently to ensure compliance. For an example of teaching classroom rules during group instruction, see the Center on the Social Emotional Foundations for Early Learning (CSEFEL) Module 1 video 1.6.

The second strategy is to teach the rules to children. To do this, use an effective teaching model, initially reinforce every occurrence of adherence to rules, use the rule statement when giving reinforcement for rule following, and state individual names when delivering praise for rule following during group activities. An example would be, “Billy, I like the way you raised your hand to answer the question”.

The Classroom Rules Checklist in this section can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of the existing rule system used in the classroom. For each item, answer “yes” or “no”; consider a “no” answer as an indication that there could be room for improvement. Use the Action column to write down some ways you could make these improvements or areas in which you need further assistance.

Bright Ideas

- Stop/Go Chart

- Begin reinforcing the use of classroom rules with mini-lessons on acceptable/unacceptable (or Stop/Go) behaviors. Have children label examples as either a stop or a go using signs or hand signals.

- Rules of Thumb

- To keep the classroom rules easy to remember, write each rule on a giant hand to display in the classroom. Hanging the hands from the ceiling keeps them visible and easy to point to for reminders. Don't forget to give a big thumbs up when a child remembers to follow a rule!

- Picture this

- Pictures, either as photographs or line drawings, can easily display the rules to children and serve as reminders for what they should be doing in the classroom. Group pictures on boards and post in a prominent location. This idea could also be used as reminders when there are specific rules for center areas. such as art or play.

Classroom Rules Checklist

| Item | Yes | No | Plan of Action/Resources Needed |

|---|---|---|---|

Are there universal expectations for the program? | |||

Have you established rules for your classroom? | |||

Does the number of rules exceed five? | |||

Are the rules stated as to what the children should "Do" rather than "Don't do"? | |||

Are the rules posted so that all children may see them? | |||

Are the rules posted so that all children may see them? | |||

Do you provide teaching to explain and demonstrate rule following behavior? | |||

Are parent informed of the expectations and rules or do they participate in their development? |

Adapted from Jack, S.L. et al (1996). An analysis fo the relationship of teachers' reported use of classroom management strategies on types of classroom interactions. Journal of Behavioral Education, 6, 67-87.

Jack, S.L. and Lindeman, D.P. (1998). Environmental support for positive behavior management. Parsons, KS: Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities.

Schedules and Transitions

Creating Supportive Environments must take into account not only the physical environment but also the programmatic structure of the classroom, which includes the schedule of activities, grouping of children and how the staff manage activities within that schedule. When one considers the schedule for the day it is extremely important that thought be given to the sequence of activities. It is important for children to have a consistent routine to follow and to prepare them for each upcoming event. Additionally, the sequence should reflect continuity among activities, and preparation for the transition between them. For example, the placement of a quieting transition activity between an active outdoor play time and an indoor circle time in which children are expected to sit, listen and be involved in a small group activity represents good sequence planning.

Transition planning should also include strategies to make the transitions smooth and trouble-free. These include using short transition times, giving a pre-signal or warning to transition (e.g., “five more minutes”, or a bell ringing), and review the rules for transition often. Also try to assign staff roles during transitions, pair children if necessary or appropriate, and reinforce model behaviors or good transition behavior. For more transition ideas, see the CSEFEL What Works Brief #4: Helping Children Make Transitions between Activities.

As the schedule for the day is developed it will be important to consider the type of staffing patterns that are needed or desired for specific activities and what strategies staff are most comfortable with and which emphasize staff strengths. For example will staff work with a set group of children and move from activity to activity with that group or will staff be responsible for a specific area of the classroom. In this case children would move from area to area as they complete an activity and a staff member would be available to welcome them to and engage them in the activity. Each of these staffing patterns has strengths and weaknesses, but thoughtful consideration must be given to this issue to provide for effective management of the classroom schedule. In some cases, it is helpful to have a schedule for staff, so that each person knows what activity he/she is responsible for and when or where to be at any given time. This is also helpful when regular staff are absent and substitute staff or volunteers are needed to participate in regular activities. See the accompanying sample schedule for a floater or staff in an afternoon program.

The classroom should provide a physical environment that is functional, responsive to the needs of the children, and engaging for the children while the schedule should facilitate and allow the children to take full advantage of learning opportunities. While a well organized classroom and schedule will not prevent all inappropriate behavior, attention to these factors will allow teachers to be in a position to effectively utilize other strategies to facilitate appropriate behavior and learning.

In addition, careful planning of classroom routines will provide numerous opportunities for children to interact with their peers and practice important social skills. See the CSEFEL What Works Brief #5: Using Classroom Activities & Routines as Opportunities to Support Peer Interaction .

The Schedules and Transitions Checklist in this section can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of the way time is allocated in the classroom. For each item, answer “yes” or “no”; consider a “no” answer as an indication that there could be room for improvement. Use the Action column to write down some ways you could make these improvements or areas in which you need further assistance.

Daily Schedule

Afternoon Program

- Floater-General Duties

- Responsible for general tone and balance of classroom.

- Greet and dismiss children.

- Assist where needed.

- Responsible for juice time.

- Help gather children for group time.

- Handle set-up and clean-up of paints and easels each day.

- Clean and tidy preparation area.

- File paintings and messages.

- Hang monthly painting show of children’s work.

- 12:15

- File name tags in cubbies.

- Set up paints.

- Select toys for game time and set aside.

- Prepare snacks, cover and set aside.

- Assist with art/science or other activities which are to be presented.

- Check lockers, file art projects, parent messages, etc.

- 12:45 - 1:30

- Greet children and parents.

- Check health needs.

- Respond to parent concerns and inquires.

- Call attention to information regarding school events and/or research.

- Take roll and assist where needed.

- Touch base with all children and staff.

- 1:30 - 2:15

- Serve snacks or delegate other staff to do so.

- Close juice.

- Wipe all surfaces and wash utensils in hot soapy water.

- 2:50 - 3:00

- Staff and children restore school and prepare for transition to group time.

- Shoes on, wet clothing filed or located.

- 3:15 - 3:35

- Set up sufficient play (games) options.

- Provide opportunities for a range of quiet, focused individual and group experiences in reasoning, problem solving, math, and language arts, as well as fine motor skills development through drawing and scribbling, manipulatives, etc.

- 3:35 - 3:45

- Assist at game time and supervise children’s departure.

- Remind parents to take home children’s projects or messages from school.

Adapted from: Wayne County Early Childhood Center, Monticello, Kentucky.

Bright Ideas

- Sammy the Sleeping Snake

- Sammy is used to make a quiet transition from one location to another, usually some distance apart (different rooms). The children carry Sammy from place to place using the handles sewn on his back. Since he's "sleeping", they have to be very quiet and move slowly so they won't wake him. Sammy can be made from fabric or pantyhose stuff with batting.

- A Barrel of Apples

- This transition activity involves moving from a quiet activity to another location. The empty apple barrel (cardboard cutout) is located near the started of the next location, or by the exit door. The apples are laminated cutouts with each child's name written on it. When the teacher calls out a name, that child takes the apple, walks to the barrel, and places the apple in it. They cutouts can easily be attached with Velcro, magnets, or tape. The theme can be adapted to any season.

Jack, S. L. & Lindeman, D. P. (1998). Environmental support for positive behavior management. Parsons, KS: Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities.

Schedules and Transitions Checklist

| Staff Child Ratio | Yes | No | Comment/Suggestions |

|---|---|---|---|

Is the schedule realistic for the number of children and adults present in the room during each activity period? | |||

Are all staff members available to help during times when children seem to need the most adult assistance? |

| Staff Child Ratio | Yes | No | Comment/Suggestions |

|---|---|---|---|

Are active and quiet times interspersed throughout the program day? | |||

Is there an appropriate balance of child-directed and teacher-directed activities? | |||

Is there a balance of structured and unstructured activities? | |||

Are children able to either observe or participate in most activities? |

| Transitions | Yes | No | Comment/Suggestions |

|---|---|---|---|

Does the schedule provide overlapping or simultaneous activities to avoid having children wait for transitions? | |||

Are children prepared for transitions before they occur (e.g., using cues, rules)? | |||

Have you defined specific responsibilities for all staff during transition times? |

| Teacher Schedules | Yes | No | Comment/Suggestions |

|---|---|---|---|

Have you defined specific tasks for all staff throughout the program day? | |||

Are staff assignments clearly posted in the classroom each day? | |||

Have you devised systems for effective communication during the program day? |

Adapted from Supporting Teams providing Appropriate Inclusionary preschool practices in Rural States (STAIRS), Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities, Parsons, KS

References and Resources

References

Algozzine, B., & Ysseldyke, J. (1992). Strategies and tactics for effective instruction. Longmont, CO: Sopris West, Inc.

Bambara, L., Spiegel-McGill, P., Shores, R., & Fox, J. (1984). A comparison of reactive and nonreactive toys on severely handicapped children’s manipulative play. Journal of The Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 9, 142 – 149.

Elmore, S. R, Vail, C. O. (2011). Effects of Isolate and Social Toys on the Social Interactions of Preschoolers in an Inclusive Head Start Classroom. NHSA Dialog, v14(1) 1-15.

Fox, L. Dunlap, G., Hemmeter, M.L., Josph, G.E., & Strain, P.S. (2003). The teaching pyramid: A model for supporting social competence and preventing challenging behavior in young children. Young Children, 58 (4), 48-52.

Hendrickson, J. M., Strain, P. P., Trembley, A., & Shores, R. E. (1981). Relationship between toy and material use and the occurrence of social interaction behaviors by normally developing preschool children. Psychology in the Schools, 18(4), 500-504.

Ivory, J. J., & McCollum, J. A. (1999). Effects of social and isolate toys on social play in an inclusive setting. Journal of Special Education, 32(4), 238-243.

Resources

Daily Schedule. Adapted from Wayne County Early Childhood Center, Monticello, KY.

Hart, L., Ed.D. (1993). 50+ Ways to Praise and Encourage a Child. In The Winning Family: Increasing Self Esteem in Your Children and Your Self (1993). Berkely, CA: Celestial Arts.

Jack, S.L., et al (1996). Adult attention and Proximity Checklist. Adapted from An analysis of the relationship of teachers’ reported use of classroom management strategies on types of classroom interactions. Journal of Behavioral Education, 6, 67-87.

Jack, S.L., et al (1996). Classroom Rules Checklist. Adapted from An analysis of the relationship of teachers’ reported use of classroom management strategies on types of classroom interactions. Journal of Behavioral Education, 6, 67-87.

Jack, S.L. & Lindeman, D.P. (1998). Bright Ideas. Adapted from Environmental support for positive behavior management. Parsons, KS: Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities.

Jack, S.L. & Lindeman, D.P. (1998). Sample Early Childhood Classroom Map. In Environmental support for positive behavior management. Parsons, KS: Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities.

McEvoy, M.A., Fox, J.J., & Rosenberg, M.S. (1991). Organizing preschool environments: Suggestions for enhancing the development/learning of preschool children with handicaps. Topics in Early Childhood Education, 11 (2), 18-28.

Nordquist, V.M. & Twardosz, S. (1990). Preventing behavior problems in early childhood special education classrooms through environmental organization. Education and Treatment of Children, 13 (4), 274-287.

Physical & Programmatic Arrangement Checklist. Adapted from Supporting teams providing appropriate inclusionary preschool practices in rural states (STAIRS), Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities. Parsons, KS

Schedules and Transitions Checklist. Adapted from Supporting teams providing appropriate inclusionary preschool practices in rural states (STAIRS), Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities. Parsons, KS

Additional Resources

Alberto, P.A., & Troutman, A.C. (1995). Applied behavior analysis for teachers (4th ed.). New York: Merrill.

Becker, W.C., Engelmann, S., & Thomas, D.R. (1975). Teaching classroom management. Chicago, Ill.: Science Research Associates.

* Brownell, C. & Kopp, C. (2007). Socioemotional development in the toddler years: Transitions and transformations. NY: Guilford Press.

* Butterfield, P., Martin, C. & Prairie, A. (2004). Emotional Connections: How relationships guide early learning. Zero to Three Press. (Book/DVD)

* Denno, D. (2010). Addressing challenging behaviors in early childhood settings: A teacher’s guide. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

* Dodge, D.T. (1991). The new room arrangement as a teaching strategy (videotape and manual). Washington, D.C.: Teaching Strategies, Inc.

Fagen, A.S., & Hill, J.M. (1977). Behavior management: A competency-based manual for inservice training. Washington, D.C.: Psychoeducational Resource Inc.

Gunter, P.L., Shores, R.E., Jack, S.L., Rasmussen, S., & Flowers, J. (1995). On the move: Using teacher/student proximity to improve student’s behavior. Teaching Exceptional Children, 28 (1), 12-14.

* Horn, E. & Jones, H. (2006). Social emotional development young children, Monograph Series No. 8. Longmont, CO: Sopris West.

Jack, S.L., Shores, R.E., Denny, R.K., Gunter, P.L., DeBriere, T.J., & DePaepe, P.A. (1996). An analysis of the relationship of teachers’ reported use of classroom management strategies on types of classroom interactions. Journal of Behavioral Education, 6, 67-87.

* Kaiser, B. & Raminsky, J. (2012). Challenging Behavior in Young Children: Understanding, preventing and responding effectively. NY: Pearson Publishing.

* Kelly, J., Zuckerman, T., Sandoval, D. & Buehlman, K. (2008). Promoting First Relationships. Seattle, WA: NCAST, University of Washington (manual, training DVD, handouts and cards).

Kerr, M.M., & Nelson, C.M. (1998). Strategies for managing behavior problems in the classroom. Columbus: Merrill.

* Strain, P. (2003). Nurturing social skills in the inclusive classroom. Teaching Toolbox (manual). Rare Visions Productions (video).

* Sandall, S. & Ostrosky, M. (1999). Young Exceptional Children Monograph Series No. 1: Practical Ideas for Addressing Challenging Behaviors. Missoula, MT: Division for Early Childhood of the Council for Exceptional Children.

Watkins, K.P. & Durant, L. (1992). Early childhood behavior management guide. West Nyack, NY: The Center for Applied Research in Education.

*These items are available from:

KITS Early Childhood Resource Center

2601 Gabriel, Parsons, KS 67357

Email: resourcecenter@ku.edu

Phone: 620-421-3067

Packet Evaluation

Please take a few minutes to complete the brief online survey above. Your feedback is central to our evaluation of the services and materials provided by KITS.